This is why the Juvenile Justice System in Pakistan is only restricted to a metaphysical standpoint…

Pakistan is one of the first twenty countries that cautiously and positively subscribed to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990 (UNCRC)[1]. By doing so, Pakistan assumed responsibility and bound itself to tend to and protect minors in various aspects of life in order to safeguard their interests and preserve the lives of these young individuals for a promising future.

Subscription to such a convention is an important necessity of our time, as the world is advancing amidst a global epidemic of ‘juvenile delinquency’. Such an agreement helps navigate and strike a balance between the rights of the child and the proportionality of the delinquency itself. Nelson, Rutherford, and Wolford (1996)[2] comment that delinquency, as ‘externalizing disorders’, is directed outward and involves behavioral excesses, such as disturbing others, verbal and physical aggression, and acts of violence. Subsequently, Bartol and Bartol (1986)[3] take a step forward and opine that legally, ‘a juvenile delinquent is one who commits an act that, by law, is considered illegal and is adjudicated “delinquent” by an appropriate court. Anything harmful to the state, the person, ethics, and more, will fall under this ambit’.

The rise in juvenile delinquency, especially in Pakistan, has been a result of a socio-economic[4] paradigm. With over three million[5] children in Pakistan living below the poverty line and being exposed to child labor, it has impacted the minds of these youngsters, leading them to develop antisocial behavior, as Mayer (1995)[6] puts it, which automatically associates them with delinquent behaviors. Other factors include peer pressure, nepotism in the feudal lordship system, and a dysfunctional legal system.

Among other implementations, juvenile justice is a highly recognized proposition in the eyes of the UNCRC. It defines juvenile justice as a ‘system of law that aims at promoting the well-being of children below the age of eighteen who come into conflict with the law, and diverting them from the criminal justice system’[7]. Similarly, it defines a child as ‘a person who has not attained the age of eighteen years’[8]. Furthermore, the UNCRC requires that the child’s best interests must be a primary consideration (Article 3), which is equally applicable in cases of juvenile justice, addressed in Article 40: ‘A child in conflict with the law has the right to receive treatment that promotes the child’s sense of dignity and worth, takes the child’s age into account, and aims at his or her reintegration into society. The child is entitled to basic guarantees as well as legal or other assistance for his or her defense. Judicial proceedings and institutional placements shall be avoided wherever possible’[9].

To give domestic validity to the aforementioned intent and enhance its effect in the country, Pakistan introduced its Juvenile Justice System Ordinance 2000 (JJSO)[10]. The Society for the Protection of the Rights of the Child (SPARC), in their article, classifies the main aim of the JJSO as ‘to rehabilitate and gradually reintegrate juveniles into society’[11]. However, this ordinance has faced its own fair share of obstacles. For instance, Article 14 of the JJSO states that the ordinance was ‘in addition to and not in derogation of any other law for the time being in practice’[12]. In simple terms, Article 14 impliees that other statutory provisions affecting the rights of children, especially those concerning juvenile delinquency, may be subject to scrutiny on a case-by-case basis. While this idea encourages a holistic view of several statutory provisions in the region, it is seen to resist the idea of ‘genuine juvenile justice’ as envisioned by the UNCRC.

One example that illustrates the above notion is the fact that while the JJSO prohibited corporal punishment of children in custody, in Punjab, the Borstal Act 1926 permits corporal punishment for male juvenile offenders in Borstal Institutions[13]. Similarly, while the JJSO prohibits the death penalty for young offenders, the 2014 lifting from death penalty[14] resulted in six juvenile offenders being executed[15].

Research study conducted by Elixir Publishers, titled ‘Causes of Juvenile Delinquency among Teenagers in the Pakistani Context 2012’[16] shows, four juveniles from Adyala Jail of Rawalpindi were detained and held responsible for offenses under the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) and subsequently punished. The juveniles include:

- Ehsanullah, aged 14 years old, dated 20-2-2011, charged with offense under: Section 302 of PPC for the murder of his friend, FIR 46.

- Muhammad Adil, aged 16 years old, dated 26-2-2006, charged with offense under: Section 9C of the Narcotics Act for carrying 10kg of hash (charas) from Islamabad to Rawalpindi, FIR 126.

- Faisal Shahzad, aged 16 years old, dated 8-26-2010, charged with offense under: Section 302 of PPC for killing his mother based on honor, FIR 205.

- Umair Ahmed, aged 15 years old, dated 17-9-2007, charged with offense under: Section 392 of PPC for mugging, FIR 257.

Successively, the Juvenile Justice System Ordinance (JJSO) is repealed with the advent of the Juvenile Justice System Act 2018 (JJSA)[17] following the influence of the Lahore High Court judgment in Ahmed v Federation of Pakistan[18]. This relatively newer act is much more promising as it aligns more closely with the UNCRC, defining the ‘best interest of the child’ and implying that this provision would be a key basis for decision-making. As described by the LUMS Law Journal Vol 6[19], this act provides suitable definitions for words such as ‘juvenile’ and ‘juvenile offender’. Under the Act, a ‘juvenile’ is considered to be a child whose offense may be dealt with in a manner different from that of an adult, while a ‘juvenile offender’ is a child who is alleged to have or who has been found to have committed an offense. Other important features include Section 5 and 7, which elaborate upon specific mandatory steps for the arrest of a juvenile offender and distinctive investigation procedures, respectively. This act also widens the spectrum of institutions under the scope of ‘Juvenile Rehabilitation Centre’, including centers such as women crisis centers, dar-ul-amaan, vocational and training centers. It discusses diversion processes, adequate juvenile courts, and even goes to the extent of implementing a policy of NO HANDCUFFING, NO PRISON, NO DEATH PENALTY.

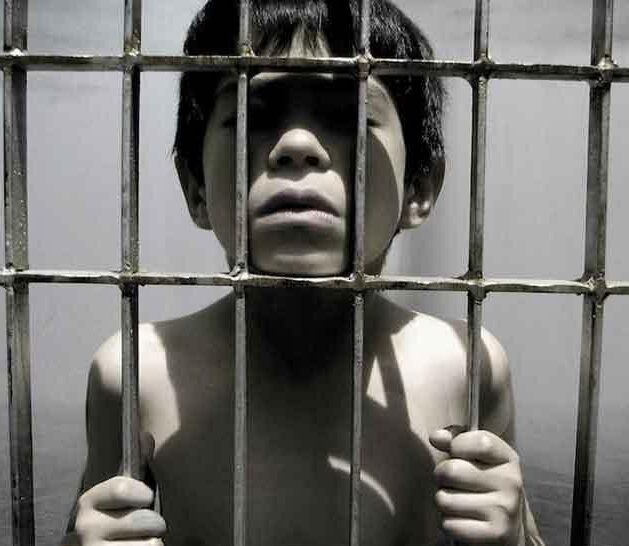

However the question of whether the Juvenile Justice System Act 2018 (JJSA) brings about practical change remains pertinent. Despite legislative reforms, the youth justice system in Pakistan continues to grapple with endless problems, including inadequate infrastructure, insufficient funding, and a shortage of human resources, resulting in overcrowded prisons. Across Pakistan, there are 113 active prisons accommodating 80,145 inmates. The situation for juvenile delinquents, women, and young children living with their imprisoned mothers is particularly dire. In nearly every prison, juvenile delinquents are incarcerated alongside adult inmates, exposing them to physical and psychological violence, intimidation, rape, and other forms of extreme abuse, sometimes even perpetrated by prison staff. (Imprisoned Child Crime – National and Provincial Child Crime Statistics)[20].

Statistics on imprisoned child crime at the national and provincial levels paint a grim picture. In 2019, according to child inmates, 1,424 incidents of child abuse were reported among offenders in prisons across Pakistan, involving 1,210 prisoners and 214 children convicted of criminal offenses. Notably, only one case of a convicted female prisoner was reported in Sindh province[21]. These figures underscore the urgent need for comprehensive reform and effective implementation of laws to protect the rights and well-being of juveniles and other vulnerable populations within the criminal justice system in Pakistan.

It should also be realized that absence of a proper Juvenile justice system has also lead to increase in crime rate. Daily Times[22] reports instances of juvenile delinquency, where a 13-year-old boy recently killed his friend in Lahore during a brawl while playing PUBG. Another incident involves a 13-year-old boy killing his 12-year-old friend during a scuffle over a video game. Additionally, a 9-year-old boy shot his aunt in the head on the orders of his uncle, after which both of them fled the crime scene. In all these instances, the government failed to implement the Juvenile Justice System Act (JJSA) with its truest intent, thus rendering juvenile justice ineffective in Pakistan.

In 2021, Huma Naz, in her Daily Times article[23], implies that the shortcomings of the Juvenile Justice System Act (JJSA) have also been responsible for increasing the crime rate among youngsters. According to her research, 1,500-2,000 minor offenders have been reported in the year 2021 alone. These individuals are then therefore suffering in confinements with zero hope for their future.

What is truly heartbreaking are the statistics quoted in a report by the Justice Project Pakistan (JPP), which states that “ten percent of death-row prisoners in Pakistan committed crimes as juveniles or minor offenders.” With more than 3,800 people currently on death row in Pakistan, it is staggering to imagine that ten percent of these inmates could have been saved by putting them through an effective corrections system. This is not simply the failure of the state’s justice system; these numbers depict our collective failure as a society and as a nation.

The irony is that Pakistan’s law does not allow death penalties for crimes committed under the age of 18, yet it also does not pay heed to the poor treatment of these children in jails, the complete denial of their rights to be rehabilitated back into society, and the long-awaited trials, which lead to the criminalization of these young minds.

Pakistan lacks rehabilitation programs for minors, and even if the fortunate ones are released, what are the chances that they will not plunge right back into crime? The absence of opportunities, the stigma of being labeled a criminal, and the lack of real hope for survival in the economic race suggest that everything is stacked against them.

Someone asked me why we should save these criminals when there are countless abandoned children on the streets, bonded laborers, and even those who were born in jails? That someone even went on to say, “they were merciless to someone and not misfortunate.” I think there is a thin line between the two, and in this scenario, it is very murky.

Dawn[24], in their paper dated August 12th, 2022, also raised similar issues and went on to say, as I quote, “When a child unfortunately becomes involved in criminal activity — often the result of conditions over which the child has no control — the consequences take the child from the prison of birth to a prison where formative growth occurs before reaching 18 years of age. And because the first few years of life crucially shape attitudes and behavior in adulthood, a juvenile offender, even when released from jail, remains a prisoner for life.”

Comparably, Saman Khan (anchor – Voice of America (VOA)[25] after an interview with Shafiq, a former juvenile prisoner, deduced that Shafiq awaited three and a half years before he was acquitted with the help of Redemption – Give Life a Chance (a nonprofit agency). In the meantime, Shafiq expressed that he was beaten, given ‘kacha khana’ (uncooked food), and had many tiffs with several older men. He was also kept in solitary confinement for about three and a half months. He recalls that there were books and computers but no one to help him educate with love and care. Aaroon Arthur[26], Director Redemption, opines that JJSA is only limited to paper up till now, and due to its shortcomings, minors such as Shafiq are being exposed to the worst of society both mentally, physically, and sexually.

This situation brings us back to the very question, is the state and society doing enough for these young offenders? Were these offenders even in their mind or did they even possess the capacity to do the crime which they are accused of? Is it okay for us to stay calm and not bother even when 90% of these juveniles still await their trial[27].

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Childhttps://www.savethechildren.org.uk/what-we-do/childrens-rights/united-nations-convention-of-the-rights-of-the-child ↑

- Nelson, C. M., Rutherford, R. B., & Wolford, B. I. (Eds.), (1996). Comprehensive and Collaborative Systems That Work for Troubled Youth: A National Agenda. Richmond, KY: National Coalition for Juvenile justice Services ↑

- https://www.worldcat.org/title/criminal-behavior-a-psychosocial-approach/oclc/899943696?referer=di&ht=edition ↑

- http://web.uob.edu.pk/uob/Journals/Balochistan-Review/data/BR%2001%202020/263-275%20Socio-economic%20Factors%20of%20delinquent%20behavior%20among%20juveniles%20in%20Baluchistan,%20Pakistan,%20Manzoor%20Ahmed.pdf ↑

- Daily Times Pakistan Report 2006 ↑

- Mayer, G. R. (1995). Preventing antisocial behavior in the schools. Journal of Applied Behavioral Analysis, 28 (4), 467- 478. ↑

- Juvenile Justice Definitionhttps://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/crc/docs/CRC.C.GC.10.pdf ↑

- Child Definitionhttps://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx#:~:text=PART%20I-,Article%201,child%2C%20majority%20is%20attained%20earlier ↑

- Article 40 UNCRChttps://www.cypcs.org.uk/rights/uncrc/articles/article-40/ ↑

- Juvenile Justice System Ordinance 2000https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/81784/88955/F1964251258/PAK81784.pdf ↑

- SPARC articlehttps://www.sparcpk.org/SOPC2019/JJSO.pdf ↑

- https://www.sparcpk.org/SOPC2019/JJSO.pdf ↑

- Pakistan Country Report, Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children: http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/countryreports/pakistan.html ↑

- The moratorium on the death penalty was lifted in December 2014, following the terrorist attack on the Army Public School, Peshawar by the TTP ↑

- Justice Project Pakistan (JPP) report: “Death Row’s Children”, 2017 ↑

- https://www.elixirpublishers.com/articles/1351503806_51%20(2012)%2010897-10900.pdf ↑

- https://na.gov.pk/uploads/documents/1519296948_886.pdf ↑

- Farooq Ahmed v. Federation of Pakistan, PLD 2005, Lahore 15 ↑

- https://sahsol.lums.edu.pk/law-journal/does-juvenile-get-better-law-time-comparative-review-new-old-juvenile-laws-pakistan ↑

- https://www.penalreform.org/blog/unearthing-the-facts-about-children-facing-the-most/ ↑

- https://www.mylegalrights.com.pk/2022/02/role-of-juvenile-justice-system ↑

- https://dailytimes.com.pk/849887/juveniles-in-pakistan-are-victimized-heres-why/ ↑

- https://dailytimes.com.pk/803097/the-rotten-juvenile-justice-system-in-the-country/ ↑

- https://www.dawn.com/news/1612403 ↑

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ik9-D9_SQis ↑

- https://pk.linkedin.com/in/aroon-arthur-31b69489 ↑

- https://www.dawn.com/news/1612403 ↑

Written by: